Originally, I titled this post My Art Journey, but I always feel titles beginning with My have a whiff of the sort of book you might write in prison after a failed coup in Munich. So, it’s just An Art Journey. One among so many others.

I’m writing it for two reasons: people keep asking me about how I got here from there, and also some of it might help younger artists grapple with the sorts of things artists grapple with.

I’m at the age now when looking back is, if not exactly encouraged, at least tolerated. As you might already know, as a wanderer, I have an interest in wayfinding and navigation. The route up a mountain can often be mysterious and tricky to navigate from below and yet, from the top looking back, it seems obvious and well-trod. I’m hoping I might make some sense of the journey by looking back down the mountain so to speak. So there’s a sneaky third reason for writing this.

When I was at school I thought I’d be an engineer. I got the grades to go to university but, in a dramatic eleventh hour volte-face, I decided I wanted to be an artist. I’ve never regretted the decision, except financially. To paraphrase Kurt Vonnegut: it’s a great way to live, but a terrible way to make a living. I figure now that following our instincts when making decisions can often lead to happier outcomes. Although maybe that depends on your instincts.

So, I’ve been painting since art school in 1981 which at the time of writing clocks up at 44 years. That’s 44 years of marriages, bereavements, epiphanies and migrations. Also 44 years of slapping paint around, and that’s what I’ll be focusing on here.

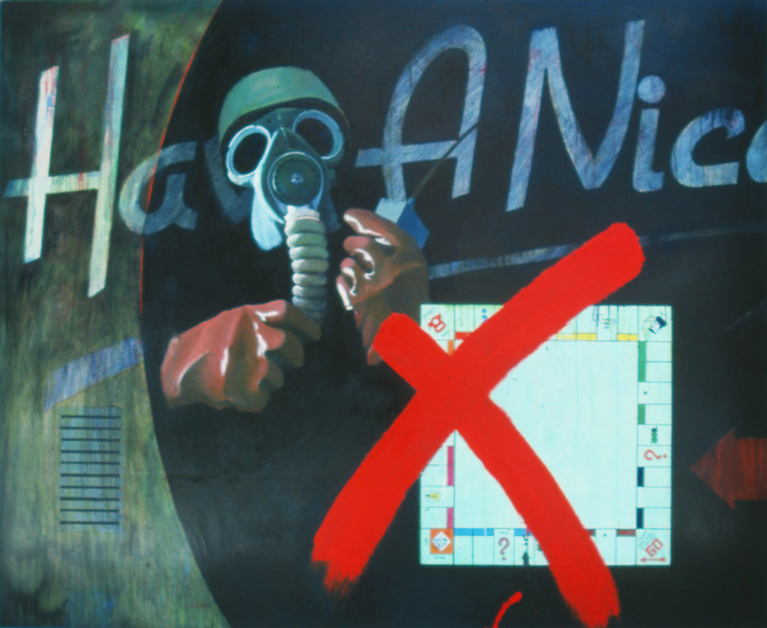

Sometimes folks ask me what my art was like at art school. Well, here’s one I prepared earlier. Much earlier. In my defence I should point out that 80s Britain was pretty bleak. Entitled Some are More Equal, this was begun at the end of 1984. The real 1984, not the book although it lifts its title from Orwell’s Animal Farm. As a young, awkward man, it was as much about social exclusion as it was about equality, and about who gets to decide who’s equal to whom. Visually I was influenced by movies like Terry Gilliam’s Brazil, and this cinematic quality led to two paintings being bought by the film critic the late Roger Ebert. The photo was taken at my degree show in available light with a hand-held 35mm camera using slide film. It’s a wonder you can see anything at all. It’s around eight foot tall and was chosen to adorn a corridor in Ninewells Hospital in Dundee. Quite why you would want to see this image on your way to surgery I do not know. Shudders.

I graduated and then, after the hangover wore off, I looked around and wondered what on earth I would do with the rest of my life. While I was wondering, I continued to paint. It’s a hard habit to break.

Below is a gallery of paintings from the 80s. You can see a theme emerging from the gloom of these terrible photographs. Shaped canvases, hinged panels, and a sort of surreal pop-art collaging on top of a dark still life stage. My favourite is probably Election Day: the dots on the angler fish are painted with luminous paint and glowed in the dark. There was no end to – depending on your point of view – my inventiveness, or my desperate quest for attention-seeking novelty. The side panels could fold shut like a sort of retable, and written on the reverse was a little passage about the angler fish which went something like: “so murky is the light at these depths that it will swallow anything that comes its way”. This and Tyrants Destroyed were among a half dozen paintings exhibited in the Cork Gallery in New York in about 1990. This was of course pre-internet and, stupidly, I didn’t keep any of the catalogues or reviews in the art papers of the time. There’s a lesson for you right there. Keep everything.

Tightly painted Monopoly boards represented destroyed cities; paper cutouts: hapless people; Spitting Image dog chew toys for Thatcher and Reagan; and a mushroom in a jar in When the Wind Blows, painted as we waited for the radiation cloud from Chernobyl to sweep over us. Happy days.

Some years later I found out that I had been part of an art movement called the Dundee Imagists, and there was an exhibition held at the university looking back at our work then.

The paintings are in roughly chronological order. The last one, My First Atomic Science Set was a development where I included actual figures. One arm is borrowed from a Caravaggio painting, and the whole thing is a nod to Joseph Wright of Derby and his celebrations of science.

Would this development signal a shift to a more figurative, narrative style? This was the end of the 80s. Everything changes in the 90s and I’ll save that for Ep2.

What a cliff-hanger.